欢迎进入基站测试中心!

Poor network reliability, perceived or real, is a primary reason subscribers leave a network, also known in the industry as “churn”. Key performance indicators (KPI) such as blocked or dropped calls and data sessions or low data throughput are monitored and are identified by network operators as the main reasons customers churn. Additionally, operators are having to overcome the multiple challenges of co-siting new LTE-A 4G technology with legacy 3G and 2G infrastructure, new base station types such as remote radio heads (RRH) using the optical CPRI interface for fronthaul, advanced MIMO transmission techniques, providing reliable in-building coverage using distributed antenna systems (DAS), increasing passive intermodulation (PIM) and interference levels and sometimes periodic mandatory regulatory testing, all while keeping installation, maintenance and optimization costs under control.

Cable and Antenna Systems

The cable and antenna system plays a crucial role of the overall performance of a Base Station system. Degradations and failures in the antenna system may cause poor voice quality or dropped calls. From a carrier standpoint, this could eventually result in loss of revenue.

While a problematic base station can be replaced, a cable and antenna system is not so easy to replace. It is the role of the field technician to troubleshoot the cable and antenna system and ensure that the overall health of the communication system is performing as expected. Field technicians today rely on portable cable and antenna analyzers to analyze, troubleshoot, characterize, and maintain the system.

C-RAN and Fronthaul

The rapid spread of smartphones and tablets together with many new Cloud services in the last decade have led to explosive growth in mobile data traffic. Operators are supporting mobile data traffic growth by increasing the bandwidth of mobile communications networks. This has been an important driver for a complete change in mobile communications systems with the adoption of the Centralized-Radio Access Networks (C-RAN), sometimes called Cloud-Radio Access Networks. Another important driver for operators has been reducing network running costs.

Backhaul

The first mobile communications backhaul was based on TDM technology (SDH/SONET and PDH) but quickly migrated to Ethernet-based packet-switched networks due to simplicity and relatively low costs. However, the asynchronous nature of Ethernet is a challenge because mobile networks require frequency synchronization across the entire network. Although TDM technology has a built-in physical layer supporting frequency synchronization, Ethernet has replaced TDM in mobile backhaul by using Synchronous Ethernet technology, which applies synchronization to Ethernet-based networks.

Baseband unit (BBU)

Traditional cell sites consisted of a ground-based radio connected to tower-mounted antennas by a long run of coaxial cable which has high loss and is vulnerable to interference. This has negative impacts on maintenance costs as equipment ages and also on system performance.

To answer the need for more throughput at lower cost, wireless network providers have moved to using a remote radio head (RRH) where the radio equipment is connected to the baseband unit (BBU) by a fiber optic cable. This provides a new level of flexibility in how the cell site is deployed, including siting the RRH at the masthead (for low RF losses) or locating the BBU at a remote location (for improved operational efficiencies).

CPRI Solutions

A flexible interface between the BBU (baseband unit) and RRH (remote radio head) is necessary to accommodate today’s new architecture. Many high speed serial communication standards are available, but without modification, none offer the high throughput, low latency and features required to support these cell site architectures.

New interface standards have been developed to support these new cell site architectures. The two interfaces that lead this charge are the Open Base Station Architecture Initiative (OBSAI) and Common Public Radio Interface (CPRI). OBSAI is the more complex of the two to implement and CPRI technology is now used in the majority of new installations. CPRI pushes the complexity into the higher layers of the system so a connection between the BBU and the RRH can be established with minimal configuration. CPRI has become the more common standard, allowing manufacturers to tailor the interface to their own requirements. The high throughput potential of later CPRI releases enables providers to futureproof their rollouts.

Effective Isotropic Radiated Power (EIRP)

The introduction of active antenna systems on 5G base stations requires engineers installing and maintaining them to use alternative measurement methods, such as effective isotropic radiated power (EIRP) for transmitter power and beam verification.

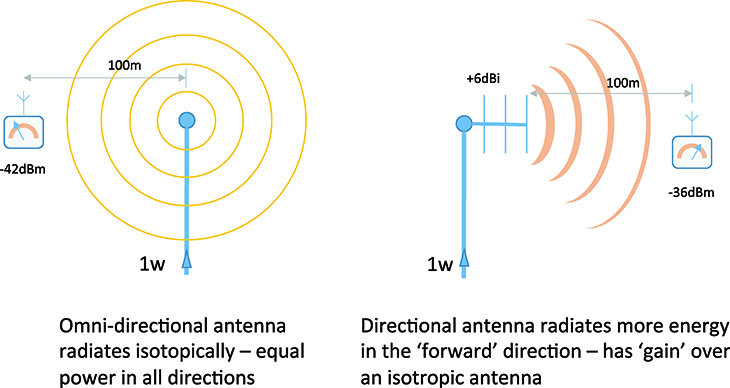

The Need for EIRP

First, let us define what is meant by EIRP. If an antenna could be made that was effectively a point source and it radiated RF energy equally in all directions (in 3D space), then the signal strength measured at a set distance would be same regardless of the direction. This antenna would then be radiating “isotropically”. Such an antenna can also be said to have unity gain, or no gain. A good 2D example of isotropic radiation would be when a pebble is dropped into a pool of water and the waves are equally dispersed in all directions.

Now, if a non-isotropic or directional antenna is used to measure the signal strength at the same distance as before and the input power was varied to get the same reading as before, then it could be said that the radiated power in that specific direction was equivalent to an isotropic antenna with a given input power.

For example, at 1 GHz and a distance of 100 m, the free space path loss is 72 dB. If a signal of 1W (+30 dBm) is fed into the isotropic antenna, the power measurement is –42 dBm (Figure 1A). If a directional antenna is used with a gain of 6 dBi in the intended or “boresight” direction, the result is a reading of –36 dBm (Figure 1B). It could be said that it is +6 dBi or 6 dB more than the isotropic antenna. Taking it further, it can be said that the directional antenna has the effective radiated power of an isotropic antenna fed with +36 dBm or 4W. In short, it has an EIRP of 4W. (Note: when measuring the gain of an antenna, it is typically given in dBi or dBs relative to an isotropic antenna.)

Practical Measurements of EIRP

Virtually all 5G base stations employ two polarized antenna arrays to improve diversity and reduce fading. Typically, they would be angled at ±45° and used in several ways. For SSB beams, the location of the UEs are unknown so it is likely that both antenna arrays would carry the same information transmitted at similar power levels. This would ensure that reception in a random location/orientation would be optimized as the UE’s antenna polarization would be unknown.

For traffic beams, the two antenna arrays can be used in a MIMO fashion to achieve multiple paths to the UE to either maximize reception quality or, under clear signal conditions, data throughput. There may be other reasons why a base station might choose to vary the signals on the two antenna arrays, such as reducing base station to base station interference or optimizing reflected signals off nearby buildings.

Therefore, in order to determine the true beam power, the power has to be measured in two orthogonal planes and then added together to give the total EIRP. The 3GPP base station test specification TS38.141 states that the two orthogonal polarizations may be measured simultaneously or separately. Using the latter method simplifies the procedure, reduces the cost of equipment, and reduces the number of elements that need to be calibrated.

Return Loss on Base Station Coverage

When designing and building cellular infrastructure, one objective is to maximize the RF signal level seen throughout the coverage area. Assuming the noise level remains constant, higher signal levels mean faster data rates and fewer dropped calls, ultimately resulting in happier customers.

In many cases, the personnel building a cell site do not control every variable necessary to ensure strong signals. Some of the variables outside the installer’s control include transmit power levels from the radio, cable type, antenna gain and antenna height. Important variables that installers do control are losses in the cable feed system due to reflections and absorption. As we all know, minimizing these losses will improve the quality of the system. But, there are points of diminishing return. Sometimes “better” may provide very

little practical benefit to customers. In times where operators are seeking sensible ways to reduce installation costs, knowing when to stop chasing that last decibel is important to understand.

In-Building Wireless

The purpose of an in-building wireless (IBW) system is to provide enhanced network coverage and/or capacity when the existing macro network is not able to adequately service the demand. Coverage may be poor due to high penetration losses caused by the building structure or due to low emissivity glass installed to improve the thermal performance of the building. In dense urban environments, adjacent buildings may create an RF barrier that blocks coverage from nearby macro sites. Tall buildings typically have poor coverage on upper floors since macro site antennas, many floors below, are specifically designed to suppress energy radiating above the horizon. Capacity may be an issue in venues such as stadiums, coliseums and convention centers where many thousands of users may be trying to simultaneously access the network.

Wireless Glossary and Dictionary

The wireless industry is constantly evolving, and so are the words and terms we use to describe its technology. Whether you’re describing the difference between W-CDMA, CDMA and TD-SCDMA… explaining applications such as line sweeping, DTF measurements or vector signal analysis as they apply to GSM, HSPDA or WiMAX… or simply looking up a term that’s new to you… Anritsu's Wireless Base Station Glossary is the place to start.

0-9 | A-B | C-D | E-G | H-M | N-R | S-Z

Base Station Industry Associations

Your community of base station and RF wireless professionals.

Speed your RF wireless network deployment or solve problems by using the experience of others working with base station testing and analysis. Use these links to connect with industry standards groups as well as Anritsu’s own Master User Group.

Base Station Industry Associations

Products

MT8213E

频率为 100 KHz 到 6 GHz 的频谱分析仪频率为 2 MHz 到 6.0 GHz 的电缆 & 天线分析仪

MT8220T

Base Station Analyzer

400 MHz - 6 GHz VNA frequency

150 kHz - 7.1 GHz SPA frequency

MS2712E

频率范围为 100 kHz ~ 4 GHz 的频谱分析仪

MS2713E

Handheld Spectrum Analyzer

9 kHz - 6 GHz frequency

1 Hz - 3 MHz resolution bandwidth

MS2720T

Handheld Spectrum Analyzer

9 kHz - 9 GHz, 13 GHz, 20 GHz,

32 GHz, 43 GHz frequency

MT1000A

- 100G Multirate Module

- 10G Multirate Module

- OTDR Module

- CPRI RF Module

Smart All-in-one Optical and Data Measurements

MT9090A

网络测试仪 MT9090A 是一款针对现场测试推出的便携式多功能用表,采用模块化结构,可以支持光纤线路、CWDM 以及千兆以太网的测试。

S412E

Land Mobile Radio

500 kHz - 1.6 GHz VNA frequency

9 kHz - 1.6 GHz SPA frequency

S331P

线缆与天线分析仪

150 kHz – 4 GHz , 150 kHz – 6 GHz

超便携

S332E

频率为 2 MHz 到 4 GHz 的电缆 & 天线分析仪频率为 100 kHz 到 4 GHz 的频谱分析仪

S361E

2 MHz ~ 6 GHz 电缆 & 天线分析仪

S362E

2 MHz ~ 6 GHz 电缆 & 天线分析仪100 kHz ~ 6 GHz 频谱分析仪S362E 的 360 度视角

MA24507A

Power Master 毫米波功率分析仪

9 kHz — 70 GHz

频率可选

MA24350A

微波 CW USB 功率传感器

10 MHz — 50 GHz

50 kHz 视频带宽

MA24340A

Microwave CW USB Power Sensor

10 MHz - 40 GHz frequency

K (male) connector

MA24330A

Microwave CW USB Power Sensor

10 MHz - 33 GHz frequency

K (male) connector

MA24126A

Microwave USB Power Sensor

10 MHz - 26 GHz frequency

True RMS Measurements

MS2850A

Spectrum and Signal Analyzer

9 kHz - 32 GHz, 44.5 GHz freq

MG3710E

100 kHz - 2.7 GHz, 4 GHz, 6 GHz frequency